A surfer’s reflections on a winter spent in the Norwegian Arctic

By Seamus Ryder

It

was a long, dark winter. The fall, as harsh and challenging as it seemed at the

time, was remembered longingly as being warm, bright and full of cheerful optimism. No one really knew when autumn ended -

I seemed to blink my eyes sometime in October, and suddenly the snow had

climbed down the final divide from between the mountains and the coast to cover

everything in sight. Back then, we had raced to the sea in the morning to meet

the rising sun. In winter, you could sleep in until noon and still wake in time

to see the sunrise – alarms were set to ensure you didn’t miss the sunset.

As

winter set in, three hour drives between fjords and mountain passes became five

hour drives through white-out (and white-knuckle) conditions. We set out on 10

hour return trips for one hour of surfing in dim, blue, light. Divine

intervention was required to line up the right combination of wind, swell, and

coastal access during the ever-vanishing window of daylight. On average, after

the summer solstice (June 21st), each day was 10 minutes shorter

than the last. In winter, the days bleed daylight at an even greater rate –

Tuesday might be close to 20 minutes shorter than the preceding Monday. Of

course, November eventually came along and then, one day, the sun simply refused

to rise. That’s when things got really interesting.

Nothing

can really prepare you for the Polar Night. Ask the locals about it and

suddenly they look at you with pity and compassion - like the look a parent

gives a young child when they tell them their dog “has gone to live on a farm”.

As the darkness approached, I was about as a naïve as a child too. I kept

telling myself it was nothing I couldn’t handle, with years of Canadian winters

under my belt and a mind that had proved itself fairly resilient to other

stressors in the past. I even maintained a strict regimen of fish oil, as the

Norwegians are apt to do, to ensure my daily dose of Vitamin D, something I

once took for granted when living beneath the Australian sun. All the fish oil

in the sea couldn’t save me. None of it really made a difference.

I

equate my experience with the Polar Night with somewhat of a mild depression.

In fact, it’s a diagnosed medical phenomenon that befalls many inexperienced

residents of the High North, sometimes referred to as Seasonal Acute Depression

(SAD). The monotony of days without day but only perpetual night takes its

toll. You lose motivation to do anything but the bare minimum. A constant fatigue

engulfs you, yet night-time (the true hours of night during which you would

regularly sleep, as distinguished from all the other hours of darkness) brings

nothing but restlessness and disturbing dreams. Even if it were somehow

possible to surf amidst the fierce winter snows and winds and the impenetrably

black abyss of the Arctic winter, I doubt I could have. I began to lose hope, and at times, I

thought I was losing my mind.

Yet,

even in darkness, there was light. At the lowest point of my slow descent into

the despair brought on by the Arctic winter, the heavens themselves opened up

and saved me. The Aurora Borealis (aka Northern Lights, Polar Lights) is one of

the greatest mysteries known to man. While scientific and technological

advancements continue to attempt to explain the spectacle as a product of solar

radiation and reactive gases in our planet’s atmosphere, they’ll never be able

to explain its otherworldly power to affect those who witness it. There are

records of its strange powers throughout history – references found in the logs

and journals of Arctic explorers, fables and legends devoted to it in the oral

traditions of the Arctic indigenous peoples. The Inuit believe that the spirits of our ancestors can be

seen dancing in the lights, and I experienced a feeling of solemn celebration

at the sight and could almost hear their whispers. To me, the Aurora was a

display of the supernatural and yet it induced a very human response. To

witness them gave me a sense of my place in the world, the universe and human

history at that precise moment in time. Despite the dark of night, I found my

way gazing up at the cosmic dance above.

Another

good thing came out of the darkness - a brotherhood was formed. I was not alone

in the Polar Night. After all, everyone living at my latitude was united in

sharing the experience, for better or worse. With surfing efforts confounded by the pitch dark of winter

snows, my surfing companions became my drinking companions. Claes (a Swede who

decided one day, at age 42, to become a nurse, buy a van, move to the Norwegian

Arctic, and learn to surf), Leon (Claes’ Swedish housemate), Victor (a heavily mustachioed,

Ecuadorian photographer), and I substituted the hours previously spent scouring

the coast for waves with hanging out in dimly lit kitchens, drinking

over-priced rum, slowly getting fat and whiling away the winter. Surfing had brought us together, but

the Polar Night made us friends.

After

five long weeks of perpetual darkness, the sun finally rose for the first time

sometime in January. Granted, it was a gradual and slow progression back to

daylight (first, the return of dim, blue light for a few hours a day, then 45

minutes of true daylight, and eventually, longer days), but nonetheless a

contagious joy spread throughout the North. Suddenly, there was hope for surf

again. The 5-hour drives through treacherous conditions remained intact, but at

least there was daylight waiting for us at the sea. Before, we may have

shivered and grimaced at the frigid, wintered Norwegian Sea before us, but now

we dove in with the same zeal with which you would approach a tropical beach

break. The snow, wind, stormy surf and sub-zero temperatures all seemed

manageable – there was light once again!

The

Polar Night had also groomed the fjords. Coastal access can be problematic in

such a sparsely developed place as the High North. In fall, we would discover

promising fjords with no roads, and so, we’d have to trudge for hours along the

shoreline only to find a set-up with promise but the wrong set of conditions.

Now, after weeks of snow and darkness that kept us away, we returned to find

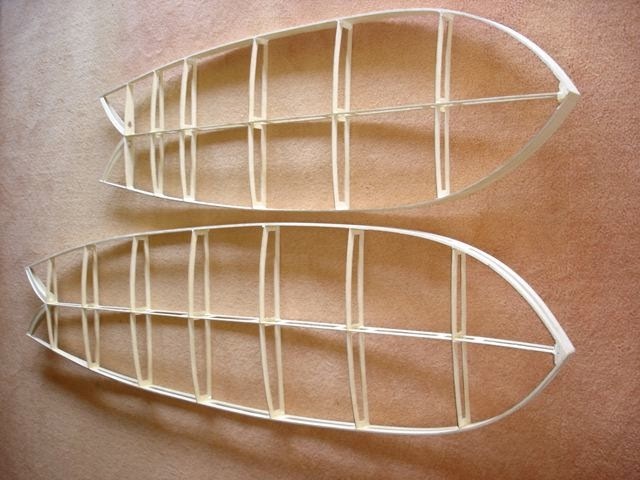

the whole coastline had essentially become one immense ski trail. With surfboards in tow, we strapped on

our cross country skis and made quick work of waist deep snow. Warmed up and

heart beating fast from the ski in, we hastily stripped down and suited up in our

thick winter wetsuits as the snow continued to fall and swapped skis for

surfboards. Changing out of our wetsuits into ski-gear post-surf was less

enjoyable, but the ski back to the van usually warmed us up again. In this way

we made the most of our Arctic lot.

In March, some academic

research in the law of the sea brought me to Svalbard, an archipelago in the

Arctic Ocean and the wildest place I have experienced on Earth. Svalbard was long regarded as a true terra nullius for most of its history.

It was used by Europeans for whaling in the 17th and 18th

centuries until they exhausted virtually all the whales. Accordingly, use

shifted to hunting, until that too dwindled with the near exhaustion of walrus,

arctic fox and the iconic polar bear. In the early 20th century, the

prospect of coal mining required the ambiguous ownership of the territory be

resolved to facilitate better regulation. Ultimately, the Svalbard Treaty was

made and recognized Norwegian sovereignty over the territory subject to unique

rights of equal access for resource exploitation by all contracting parties.

Today, coal mining is following the way of whaling and hunting and has seen a

great downturn in production. But just like the rest of Svalbard’s history, as

one resource is exhausted another is pursued. In this present era the

combination of climate change and technological advancements is opening up the

possibility of lucrative fishing opportunities and oil and gas production in

the maritime zones that surround the archipelago. Significant uncertainty exists in determining the legal

regime that will govern these opportunities, as some States argue the

-->

aging Svalbard Treaty

entitles them to certain rights to undertake resource exploitation while others

argue the Svalbard Treaty is trumped by the modern international law of the sea.

The purpose of my visit was to explore these issues in detail

Svalbard’s

name, translated literally, means “cold shores”, and it is an accurate title.

The temperature hovered around a balmy -20 degrees Celsius for the duration of

my visit, but the days were sunny, with minimal wind. The hardy locals assured

me this was unusually warm weather for the time of year and pointed out that

the harbor was ice-free earlier in the year than ever before. Climate change is

an inescapable reality in this part of the world. All around there are signs of

its effects, from the ice-free harbours that shouldn’t be to unseasonable

temperatures. There is some cruel irony in the fact that hunting activities

that brought wildlife in the area to near collapse were replaced by coal

mining. As hunters traded in guns for shovels and picks populations were able

to recover, but the same mining has played a role in the production of fossil

fuel and greenhouse gas which is drives global warming, which may prove a much

bigger threat. Thanks in part to an increased interest in eco-tourism and

related conservation efforts; the polar bear has been able to avoid collapse.

Today, it is estimated that some 5000 polar bears outnumber the 3000 human

residents of Svalbard. That news left me very uneasy on a dogsled tour far from

the relative safety of the population centre, but it is good news for the

bears. Still, many wonder whether it will be enough to secure the future of the

polar bear, and other Arctic wildlife, in the face of accelerated and

unprecedented changes to their climate and habitat.

When

I reflect back on these experiences and my first winter in the Arctic, I

realize the importance of adaptability. Whether it’s personal adaptation to the

Polar Night, or adapting to winter surfing in the Arctic by donning thick

wetsuits and cross-country skis, the key to success often comes down to the

ability to make adjustments and work with the conditions and resources on hand.

This remains true on a much larger scale. The case of Svalbard illustrates that

climate change and globalization are fundamentally transforming the strategic

and economic position of the Arctic. Retreating sea ice allows access to vast

commercial opportunities, such as the development of offshore oil and gas

reserves and large-scale industrial fisheries. Successful regulation of these

emerging opportunities depends on the adaptability of legal regimes to reflect

changing environmental values and evolving knowledge of the fragile Arctic

ecosystem. Ultimately, the continued success of our Arctic will depend on its

ability to adapt to climate change and increased human activity and use. To

conclude on a positive note, if my winter in the Arctic taught me anything, it

was that the ability of human beings to adapt is astonishing. When we have a

goal in mind and are confronted by change, whether it’s surfing in the middle

of Arctic winter or protecting the Arctic environment from climate change,

chances are we can find a way to do it.

Seamus Ryder has found waves in unlikely places since the day he started surfing. Born and raised outside of Toronto, his first surf was on Lake Ontario, one of Canada’s Great Lakes. The stoke he discovered surfing freshwater wind-slop informed his decision to attend university in Halifax, Nova Scotia where he spent 4 years scouring the many points, bays, and harbours of the Canadian Maritimes. After obtaining his undergraduate degree in the broad and vague field of “management” he did a brief stint as a professional sailing coach in the Caribbean, and an even briefer stint as a garbage man back in Canada. In 2011 he moved to the Gold Coast of Australia to attend law school. There, he obtained casual employment at a busy, family-owned bakery and the Patagonia Burleigh Heads shop. Since September, he has been living in the Norwegian Arctic, where he is studying a Master of Laws in the Law of the Sea at the University of Tromsø, the world’s northernmost university. |

ryder.seamus@gmail.com

I met Seamus at the Patagonia store at Burleigh. A very interesting guy who loved the outdoors and surfing.It has been great to hear his story and share this with you.

No comments:

Post a Comment